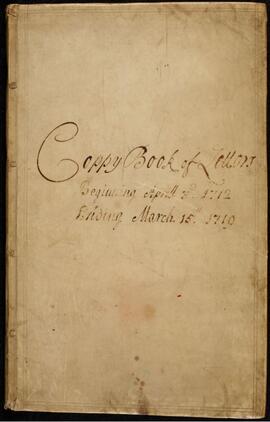

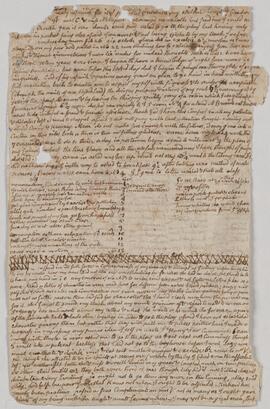

Manuscript letter book bound in vellum, containing copies of letters sent by Thomas White. The letters are mostly concerned with land transactions, the collection of rent and other matters relating to the management of White’s extensive portfolio of properties. His concerns in Ireland feature prominently, particularly his attempts to find new tenants for his Limerick estates and an agent to collect their rents. One Irish tenant, George Evans, proved exceptionally troublesome. When their long-standing dispute over unpaid rent was finally resolved, White rushed to praise Henry Dallway ‘for the services you have don [sic] me in my affair with Coll Evans, we have gained a glorious victory over a difficult Enemy’ (17 Jul 1707, p. 106).

White was very particular about his money, complaining in one instance of a remittance being a shilling short (4 Dec 1708, p. 139) and pointing out to his Irish agent Christopher Tuthill that ‘You are not very exact in your accounts as I can perceave [sic] by the mistakes you had made to your own disadvantage’ (25 Jan 1708/9, p. 145). Yet, he was no miser. In a letter to his aunt, White notes that ‘It is far from my Temper to pinch Servants in their allowance, I should rather take a pleasure to see them thrive.’ (11 Sep 1711, p. 240). When building a new barn, he instructed the contractor William Wright to ‘doe every thing well, and lett all your work be very Substantiall and the materialls good, & if you wrong me in any thing lett it be only in the price’ (23 December 1710, pp. 216-217). Likewise, although an astute businessman who had no hesitation to resort to the long hand of the law when required, White was also quite reasonable in his dealings. In 1709, he accused a Mr Peartree for abusing and mismanaging his woods and threatened the man with a law suit, expounding that ‘in case it comes to a Tryall I shall then expect whatever is awarded me besides the Costs, & there I hope it will be considered not what Benifitt he has don [sic] to himself but what prejudice he has don to me & those that come after me. The punishing him I reckon a price of justice due to mankind, That other persons may be discouraged from the like practises & that future Generations may not Suffer for want of Tymber’. However, when Peartree capitulated without recourse to a trial, White immediately and willingly accommodated his request to defer the payment of damages from midsummer to Michaelmas (2 June 1709, p. 165).

Hovering in the background of White’s business endeavours is the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). The letter book reveals the many ways in which the ongoing conflict affected the financial markets and frustrated land transactions. In the wake of rumours of imminent peace in May 1709, White notified Messrs Meade & Copley of his decision to ‘defer sending you the foul Draft of your Lease in confidence of a speedy peace, for Since the Preliminaries are all agreed, & that it is very probable it will be proclaimed & ratified in a short time, I think it better for us both to defer the Leases till then’. (26 May 1709, p. 163). A mere six weeks later, he was forced to write again to regret that ‘The hopes of a peace being contrary to every bodys expectation blown over, ’tis now so uncertain when that happy day will come that I think it improper to defer the Leases till that time’ (7 Jul 1709, p. 167). At least he did not go as far as the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough, who ‘were So confident of an undoubted peace that the following Inscription was put upon one of the foundation Stones of the House now building at St Jameses… viz This Stone was laid by John & Sarah Duke & Dutchess [sic] of Malbourough [sic] in the Year of peace’ (14 Jul 1709, p. 168).

Thomas White’s observations are not limited to business transactions. Court gossip and current affairs also feature prominently. White provides a vivid account of the damage done by the great storm of 1703, which claimed the life of Rear-Admiral Basil Beaumont (30 Nov 1703, pp. 24-25), and describes in some detail the harshness of the winter of 1708-09 during which the Thames River ‘has been thrice frozen over’ (1 Mar 1708/9, p. 152). The last-mentioned letter also contains a graphic account of Mr Lythe, ‘the Master of St Dunstans Coffee house’ and his attempts ‘to destroy himself by three severall deaths in the Space of a Quarter of an hour’; and a fight between two men, of whom one was killed, ‘upon no other Quarrel than a dispute which had the most beauty of the 2 maids of honour’. He refers to the vicious attack against Dissenters in a sermon preached by the high church Anglican clergyman Henry Sacheverell at St Paul’s Cathedral in November 1709 and his subsequent impeachment by the House of Commons (21 Feb 1709/10, p. 185; 4 April 1710, p. 188). No fewer than three letters (28 Dec 1710, 13 Jan 1710/11 and 18 Jan 1710/11) mention the death of the wealthy plantation owner Francis Tyssen the younger and the contents of his will, which left his entire estate of £300,000 to his eldest son and only nominal sums to his other six children. In addition to ignoring his offspring, Tyssen gave short shrift to the poor. ‘Most People’, White noted in the second of these letters to his friend and distant relative Sigismund Trafford, ‘are of your opinion that a Gift for the Education of poor Children or Some such Charity would have been a commendable Legacy for a man of his vast Estate’ (p. 219). There are also several letters on the series of state lotteries in 1710-1711 established to raise government revenue for the War of the Spanish Succession and the pandemonium they caused when people scrambled to purchase the tickets issued for sale. White was among the eager participants, but after several disappointing rounds was obliged to concede that ‘I doe not find that I am like to grow rich by Lotterys’ (10 Nov 1711, p. 244).

Many of Thomas White’s letters are addressed to friends and relatives, among them his maternal aunt, Mrs Margaret Crowther, and his friend Sigismund Trafford, whose second wife was distantly related to White. The letters to Trafford, an older and much wealthier man, are simpering and flattering in tone, and refer to Trafford as ‘my noble patron’. Court gossip features prominently in these missives. ‘I have no room to say any thing of the Birthnight Ball’, White reported to his friend on 22 February 1710, ‘only that the Lady Louisa Lennox Daughter to the Duke of Richmond bore away the Ball for Beauty & appeared So charming that her Lover the Earl of Berkly [sic] could live no longer without her, for they were married the next Day.’ (p. 226).

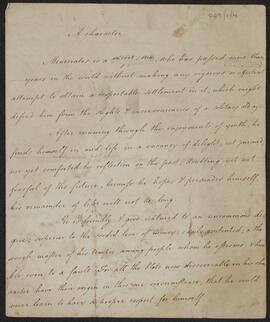

Letter dealing with private family matters are more serious in tone. White had not yet married at the time the letter book was compiled, and expressed concern that ‘good wives are so scarce that I am afraid I shall live to be an old Batchelour, if the World is so mercifull as not to think me one already.’ He also describes himself as ‘a Batchelour with more than the cares of a married man’ (4 Apr 1710, p. 188). Some of these cares were the consequence of the hardship experienced by his sister whose husband, Bedingfield Heigham, was not only of a violent temper but also careless in his financial affairs. White’s letters reveal that Heigham and his family were evicted from their house at Dalstone and that he subsequently experienced a spell in a debtors’ prison (see 18 Aug 1710, pp. 202-203). White went to considerable lengths to ensure the comfort and safety of his sister and nieces but felt no such compunction towards her unruly husband. ‘Since I wrote you last’, White relates in a letter to his aunt, ‘my Sister & I have had a wonderfull deal of perplexity with the perverse man. He has been as troublesome as he could possibly contrive to be. …our Affairs are now put into Such a posture, that I hope we Shall enjoy more quiet for the future, than We have don of late’ (26 Feb 1711/12, p. 256). All in all, the letter book provides remarkably rich and varied insights into life in the first decade of the eighteenth century.

Thomas White’s correspondents, in alphabetical order, are as follows:

Caleb Avenant, Worcester

Richard Avenant, Worcester (father of Caleb)

Joseph Bandon, ‘at Newcastle near Lymrick’

Jacob Beaufoy, ‘either at Archangle [sic] or Moskow in Russia’

James Boys, Coggesshall, Essex

John Brand

Thomas Bright ‘at Netherhall near Bury in Suffolk’

John Butler

John Carter, Aldermanbury, [London]

Hannah Collins, Shelsley, Worcestershire

John Cooke, ‘Lashleys near Steeple Bumpstead in Essex’

John Copley, Newcastle, Limerick

John Corder, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

[Margaret] Crowther, Thomas White’s maternal aunt

Henry Dalwey [also Dallway], Dublin

Joseph Deavonsheir

John Dickings [?]

William Eaton, Kingsland [London]

George Evans, Limerick

William Glascock, ‘at Hasso Bury near Bishops Stafford in Essex’

James Gould, Marestreet, Hackney

Mr Hargrave

W. Harris, Dalstone, Hackney

Joseph Hull, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

Thomas Hunt, ‘in New Court in Swithins Lane London’

Edward Jackson, Salop

Thomas King, Hackney

Williamson Lloyd, Colchester

Andrew Meade, ‘at Newcastle near Lymrick’

William Molmouth, Lincoln’s Inn

Chester Nance, Trengoff, near Fowey, Cornwall

Robert Nettles, Limerick

John Newton, attorney-at-law in Colchester

Richard Norris, ‘Merchant in Leverpoole’

Charles Odell, Limerick

John Peisson, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

Richard Price, ‘at Ryslipe, near Harrow with in Middlesex’

Valentine Quin, [Adare,] Limerick

[Mary] Ram, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

William Ram, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

Mr Savil, ‘merchant in Colchester’

Joseph Sewell

Benjamin Smythe

Sigismund Trafford ‘at Dunton Hall in Tidd St Mary’s’

Edward Trotman

Christopher Tuthill, Limerick

Hannah Tuthill, Limerick

Alexander Walford

Samuel Weaver

Philip Wheake, ‘at Mrs Frosts near the Colledge Gate in Winchester’

Henry Widenham, [Court, Kildimo,] Limerick

William Wright, Nayland, Suffolk

Jer. [Jeremiah?] Yates

The letter book contains White’s own pagination throughout, but there is an error in numbering, with p. 183 appearing twice.