List of wardships, leases, licences and offices granted to George Sexten between 1605/6 and 1623. A comment at the bottom of the page notes that ‘being doubtful that the above named George Sexten was of the family of Edmond Sexten of Limerick this sheet was omitted to be bound in the collection relative to the said Edmond.’ Originally inserted between the pages of P51/1/3.

Pery family, Earls of LimerickManuscript bound in vellum, written in secretary hand and by the same hand as P51/1/1, so presumably Edmond Sexten the younger (1594-1636). The manuscript is in two parts. The first part, dated 1629, is paginated from 1 to 504 and comprises lines copied from the Bible, with the relevant book, chapter, and verse provided at the start of each line. The copied texts are arranged under various headings, such as 'Abraham & Sarah', 'Bees', 'Ezra', 'Fraillty', 'Fraude', 'Free Will', 'Hezekiel', 'pride', 'purgatory', 'Sabath', 'Titus', 'Visitations' and 'Youth'. The headings appear in no particular order in the main body of the text but have been collated into an alphabetical index of six un-paginated pages at the start of the book. The second part, dated 1627, is paginated from 1 to 287 and is similar in content to the first part. An index for the headings has been begun at the end of the book, but only extends to entries for the letter A.

Pery family, Earls of LimerickInquisition bound in vellum concerning the lands of Edmond Sexten, who died 10 March 1636/37, acknowledging that he died possessed in fee tail of the site of the dissolved monastery of Blessed Virgin Mary and St Edward (also called Holy Cross), and various lands in Limerick city, of which the inquisition gives details. The ownership passed to his eldest son Nicholas, who died 1 January 1637/38. The inquisition further acknowledges that the lands now belong to Christopher Sexten, Edmond Sexten’s second son. For an abstract of this document, see P51/1/3.

Pery family, Earls of LimerickPaginated manuscript, with an un-paginated table of contents, bound in tooled leather covers and embossed on the spine Historical Notices of the Sexten Family & City of Limerick. The contents constitute a copy in copperplate script of P51/1/1, lacking the pedigrees.

Pery family, Earls of LimerickPaginated 17th-century manuscript in secretary hand, bound in 19th-century tooled leather covers and embossed on the spine Historical Notices of the Sexten Family & City of Limerick. Pages 1-15 contain an additional set of pagination, which runs from 47 to 61. The manuscript comprises primarily transcripts made by Edmond Sexten the younger (1595-1636) of letters and petitions (mostly in English, with some items in part or fully in Latin), which his grandfather Edmond Sexten the elder (1486-1555) had collected in order to defend himself against allegations that ‘my service to the kinge majestie is deemed... not to be such as did deserve the bountifull remuneration of his heighnes unto me’ and to prove that ‘my service was freely doone without receavinge wages or hire of the king majestie as others dothe’. In addition to letters and petitions, the transcribed items include a narrative of the costs and charges incurred by Sexton in the King’s service; a list of havens, rivers, creeks, places of importance, territories and lordships with their landlords ‘from Lupes head which is the further land a seaboord by north the river of Limerick as also within the said river’; a declaration of the proportions of Ireland; and King John’s, Queen Elizabeth’s and King James I’s charters to Limerick. To the abovementioned transcripts, Edmond Sexten the younger has added copies of letters and petitions relating to his own disputes with Limerick Corporation, primarily concerning the immunity of the lands of the dissolved abbeys of St. Mary’s and St Francis’s, which had come into his grandfather’s possession in 1537, and whether Sexten alone, or the parish generally, was responsible for the upkeep of the church of St John the Baptist, Limerick, whose tithes were appropriate to St Mary’s. In addition to transcripts of formal documents, the manuscript contains a list of books in the possession of Edmund Sexten the younger, grouped under the headings of 'Divinyty', 'History & other bookes of morallyty', 'Scoole bookes', and 'Lawe bookes'; a list of lord deputies and governors of Ireland, and of the mayors, bailiffs, and high sheriffs of Limerick from 1154 to 1636; and pedigrees of branches of the Sexten family descending from Denis Sexten and Simon Sexten, and of the Golde, Comyn, Mortagh, White, and Arthur families of Limerick. To the list of lord deputies mentioned above has been added a short account dated 22 May 1641 by Edmond Sexten’s son Christopher Sexten relating to the deaths and funerals of his father, daughter Jean (who died of smallpox), and eldest son Stephen, and the burning of his tenements in St Francis’s Abbey in Limerick, all of which events occurred in 1636.

Pery family, Earls of LimerickManuscript entitled ‘The Irish Establishment’ comprising 44 gilt-edged leaves totalling 88 pages, 12 of which are blank, in Cambridge panel calf binding contemporaneous with the contents. The document bears the official title ‘Anne R. An Establishment or List containing all Payments to be made for Civil Affairs from the Twenty fifth day of March 1704 in the Third Year of our Reign for the Kingdom of Ireland.’ It is one of several copies of a formal register of annual payments to be made to maintain the civil and military offices in Ireland at the expense of the sovereign.

The document commences with the civil list, outlining masters’ fees and other expenditure of the courts of the Exchequer, Queen’s Bench, Chancery and Common Pleas and those of the officers and ministers attending the state, customs officers, commissioners of appeals and non-conforming ministers. Also listed are payments towards perpetuities and pensions, the upkeep of lighthouses and payments made out of the concordatum fund for ‘extraordinaries’, such as ‘keeping poor Prisoners & Sick & Maimed Soldiers in Hospitals’. There is also a 13-page list of the names of French soldiers to whom pensions were to be paid following the disbanding of the French regiments that served in Ireland.

The civil list is followed by the military list, which includes allocations of money towards military contingencies and incidents and the maintenance and upkeep of regiments of horse, dragoons and foot and superior and inferior officers in charge of the Ordnance. The third and final list records payments to be made to half-pay officers and governors of garrisons, military pensions and the annual charge for maintaining and upholding all the barracks in the four provinces of Ireland. The document also provides a summary of increases and decreases in certain annual payments.

The manuscript is either incorrectly bound, or faithfully copied from an incorrectly bound version. Text on p. 56 ends mid-sentence and continues on p. 73. Pages 57-72 should follow p. 73, except for pp. 71-72, which should follow p. 80.

A number of previous owners have left their mark on the document. These include Simon Cavan, who signed p. 88 with the note ‘Simon Cavan his Book Anno Domini 1785’. The signature ‘H. Cotton’ appears on the endpaper at the beginning of the book and on the title page. This was Henry Cotton (1789-1879), Archdeacon of the Diocese of Cashel from 1824 until 1872, who previous to that appointment served in Cashel as librarian at the Bolton Library and domestic chaplain to his father-in-law Richard Laurence, who was appointed Archbishop of Cashel in 1822. There are no shelf or other marks to identify this particular volume as having ever formed part of the Bolton Library and must therefore have been part of Cotton’s private book collection.

The endpaper and flyleaf at the beginning of the book bear the stamp ‘C. A. Vignoles’ left by the very Reverend Charles Augustus Vignoles (1789-1877), Dean of Ossory and Dean of the Chapel Royal, Dublin, a fourth-generation Huguenot from Portarlington. Finally, the inside cover is signed ‘Herbert C. C. Uniacke Clogheen Co Tipperary December 1903’. This was Lieutenant General Sir Herbert Crofton Campbell (1866-1934), an officer of the Royal Artillery.

Anne, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (1665-1714)Manuscript letter book bound in vellum, containing copies of letters sent by Thomas White. The letters are mostly concerned with land transactions, the collection of rent and other matters relating to the management of White’s extensive portfolio of properties. His concerns in Ireland feature prominently, particularly his attempts to find new tenants for his Limerick estates and an agent to collect their rents. One Irish tenant, George Evans, proved exceptionally troublesome. When their long-standing dispute over unpaid rent was finally resolved, White rushed to praise Henry Dallway ‘for the services you have don [sic] me in my affair with Coll Evans, we have gained a glorious victory over a difficult Enemy’ (17 Jul 1707, p. 106).

White was very particular about his money, complaining in one instance of a remittance being a shilling short (4 Dec 1708, p. 139) and pointing out to his Irish agent Christopher Tuthill that ‘You are not very exact in your accounts as I can perceave [sic] by the mistakes you had made to your own disadvantage’ (25 Jan 1708/9, p. 145). Yet, he was no miser. In a letter to his aunt, White notes that ‘It is far from my Temper to pinch Servants in their allowance, I should rather take a pleasure to see them thrive.’ (11 Sep 1711, p. 240). When building a new barn, he instructed the contractor William Wright to ‘doe every thing well, and lett all your work be very Substantiall and the materialls good, & if you wrong me in any thing lett it be only in the price’ (23 December 1710, pp. 216-217). Likewise, although an astute businessman who had no hesitation to resort to the long hand of the law when required, White was also quite reasonable in his dealings. In 1709, he accused a Mr Peartree for abusing and mismanaging his woods and threatened the man with a law suit, expounding that ‘in case it comes to a Tryall I shall then expect whatever is awarded me besides the Costs, & there I hope it will be considered not what Benifitt he has don [sic] to himself but what prejudice he has don to me & those that come after me. The punishing him I reckon a price of justice due to mankind, That other persons may be discouraged from the like practises & that future Generations may not Suffer for want of Tymber’. However, when Peartree capitulated without recourse to a trial, White immediately and willingly accommodated his request to defer the payment of damages from midsummer to Michaelmas (2 June 1709, p. 165).

Hovering in the background of White’s business endeavours is the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). The letter book reveals the many ways in which the ongoing conflict affected the financial markets and frustrated land transactions. In the wake of rumours of imminent peace in May 1709, White notified Messrs Meade & Copley of his decision to ‘defer sending you the foul Draft of your Lease in confidence of a speedy peace, for Since the Preliminaries are all agreed, & that it is very probable it will be proclaimed & ratified in a short time, I think it better for us both to defer the Leases till then’. (26 May 1709, p. 163). A mere six weeks later, he was forced to write again to regret that ‘The hopes of a peace being contrary to every bodys expectation blown over, ’tis now so uncertain when that happy day will come that I think it improper to defer the Leases till that time’ (7 Jul 1709, p. 167). At least he did not go as far as the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough, who ‘were So confident of an undoubted peace that the following Inscription was put upon one of the foundation Stones of the House now building at St Jameses… viz This Stone was laid by John & Sarah Duke & Dutchess [sic] of Malbourough [sic] in the Year of peace’ (14 Jul 1709, p. 168).

Thomas White’s observations are not limited to business transactions. Court gossip and current affairs also feature prominently. White provides a vivid account of the damage done by the great storm of 1703, which claimed the life of Rear-Admiral Basil Beaumont (30 Nov 1703, pp. 24-25), and describes in some detail the harshness of the winter of 1708-09 during which the Thames River ‘has been thrice frozen over’ (1 Mar 1708/9, p. 152). The last-mentioned letter also contains a graphic account of Mr Lythe, ‘the Master of St Dunstans Coffee house’ and his attempts ‘to destroy himself by three severall deaths in the Space of a Quarter of an hour’; and a fight between two men, of whom one was killed, ‘upon no other Quarrel than a dispute which had the most beauty of the 2 maids of honour’. He refers to the vicious attack against Dissenters in a sermon preached by the high church Anglican clergyman Henry Sacheverell at St Paul’s Cathedral in November 1709 and his subsequent impeachment by the House of Commons (21 Feb 1709/10, p. 185; 4 April 1710, p. 188). No fewer than three letters (28 Dec 1710, 13 Jan 1710/11 and 18 Jan 1710/11) mention the death of the wealthy plantation owner Francis Tyssen the younger and the contents of his will, which left his entire estate of £300,000 to his eldest son and only nominal sums to his other six children. In addition to ignoring his offspring, Tyssen gave short shrift to the poor. ‘Most People’, White noted in the second of these letters to his friend and distant relative Sigismund Trafford, ‘are of your opinion that a Gift for the Education of poor Children or Some such Charity would have been a commendable Legacy for a man of his vast Estate’ (p. 219). There are also several letters on the series of state lotteries in 1710-1711 established to raise government revenue for the War of the Spanish Succession and the pandemonium they caused when people scrambled to purchase the tickets issued for sale. White was among the eager participants, but after several disappointing rounds was obliged to concede that ‘I doe not find that I am like to grow rich by Lotterys’ (10 Nov 1711, p. 244).

Many of Thomas White’s letters are addressed to friends and relatives, among them his maternal aunt, Mrs Margaret Crowther, and his friend Sigismund Trafford, whose second wife was distantly related to White. The letters to Trafford, an older and much wealthier man, are simpering and flattering in tone, and refer to Trafford as ‘my noble patron’. Court gossip features prominently in these missives. ‘I have no room to say any thing of the Birthnight Ball’, White reported to his friend on 22 February 1710, ‘only that the Lady Louisa Lennox Daughter to the Duke of Richmond bore away the Ball for Beauty & appeared So charming that her Lover the Earl of Berkly [sic] could live no longer without her, for they were married the next Day.’ (p. 226).

Letter dealing with private family matters are more serious in tone. White had not yet married at the time the letter book was compiled, and expressed concern that ‘good wives are so scarce that I am afraid I shall live to be an old Batchelour, if the World is so mercifull as not to think me one already.’ He also describes himself as ‘a Batchelour with more than the cares of a married man’ (4 Apr 1710, p. 188). Some of these cares were the consequence of the hardship experienced by his sister whose husband, Bedingfield Heigham, was not only of a violent temper but also careless in his financial affairs. White’s letters reveal that Heigham and his family were evicted from their house at Dalstone and that he subsequently experienced a spell in a debtors’ prison (see 18 Aug 1710, pp. 202-203). White went to considerable lengths to ensure the comfort and safety of his sister and nieces but felt no such compunction towards her unruly husband. ‘Since I wrote you last’, White relates in a letter to his aunt, ‘my Sister & I have had a wonderfull deal of perplexity with the perverse man. He has been as troublesome as he could possibly contrive to be. …our Affairs are now put into Such a posture, that I hope we Shall enjoy more quiet for the future, than We have don of late’ (26 Feb 1711/12, p. 256). All in all, the letter book provides remarkably rich and varied insights into life in the first decade of the eighteenth century.

Thomas White’s correspondents, in alphabetical order, are as follows:

Caleb Avenant, Worcester

Richard Avenant, Worcester (father of Caleb)

Joseph Bandon, ‘at Newcastle near Lymrick’

Jacob Beaufoy, ‘either at Archangle [sic] or Moskow in Russia’

James Boys, Coggesshall, Essex

John Brand

Thomas Bright ‘at Netherhall near Bury in Suffolk’

John Butler

John Carter, Aldermanbury, [London]

Hannah Collins, Shelsley, Worcestershire

John Cooke, ‘Lashleys near Steeple Bumpstead in Essex’

John Copley, Newcastle, Limerick

John Corder, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

[Margaret] Crowther, Thomas White’s maternal aunt

Henry Dalwey [also Dallway], Dublin

Joseph Deavonsheir

John Dickings [?]

William Eaton, Kingsland [London]

George Evans, Limerick

William Glascock, ‘at Hasso Bury near Bishops Stafford in Essex’

James Gould, Marestreet, Hackney

Mr Hargrave

W. Harris, Dalstone, Hackney

Joseph Hull, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

Thomas Hunt, ‘in New Court in Swithins Lane London’

Edward Jackson, Salop

Thomas King, Hackney

Williamson Lloyd, Colchester

Andrew Meade, ‘at Newcastle near Lymrick’

William Molmouth, Lincoln’s Inn

Chester Nance, Trengoff, near Fowey, Cornwall

Robert Nettles, Limerick

John Newton, attorney-at-law in Colchester

Richard Norris, ‘Merchant in Leverpoole’

Charles Odell, Limerick

John Peisson, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

Richard Price, ‘at Ryslipe, near Harrow with in Middlesex’

Valentine Quin, [Adare,] Limerick

[Mary] Ram, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

William Ram, Stoke, near Nayland, Suffolk

Mr Savil, ‘merchant in Colchester’

Joseph Sewell

Benjamin Smythe

Sigismund Trafford ‘at Dunton Hall in Tidd St Mary’s’

Edward Trotman

Christopher Tuthill, Limerick

Hannah Tuthill, Limerick

Alexander Walford

Samuel Weaver

Philip Wheake, ‘at Mrs Frosts near the Colledge Gate in Winchester’

Henry Widenham, [Court, Kildimo,] Limerick

William Wright, Nayland, Suffolk

Jer. [Jeremiah?] Yates

The letter book contains White’s own pagination throughout, but there is an error in numbering, with p. 183 appearing twice.

White, Thomas (1676-1742), English solicitor and landownerMap survey by Robert Colvill of part of the lands of Knocknamonee [Knocknamona] in possession of John McDavid on a scale of 40 perches to an inch.

Looney, Timothy (Tim) (1914-1990), local historianMap survey by Robert Colvill of Lady Shelburn’s part of Dromcommer [Dromcummer Beg] on a scale of 40 perches to an inch.

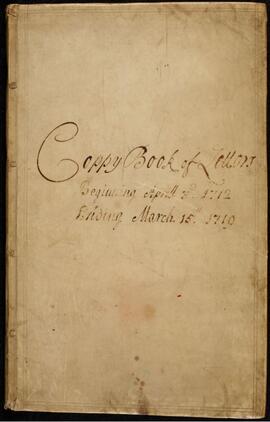

Looney, Timothy (Tim) (1914-1990), local historian3 April 1712-15 March 1719/20

Manuscript letter book bound in vellum, containing copies of letters sent by Thomas White. The book is a sequel to P25/1 but its contents bear a much stronger emphasis on family affairs and topical news than business affairs, which dominated the first volume.

Thomas White continues to follow the progress of the Spanish War of succession and observes that ‘wee live in an age of so much uncertainty, that it is a difficult matter to know what to believe’ (15 May 1712, p. 3). He also makes observations on the political fallout of the controversy surrounding the subsequent peace negotiations, which led to the impeachment of Robert Harley (Earl of Oxford), Henry St John (1st Viscount Bolingbroke) and others in 1715 and the Jacobite rising of 1715-16 and the heightened atmosphere it created across the country. He makes mention of the hanging for treason of William Paul, a clergyman and John Hall, Justice of the Peace for Northumberland and the ‘virulent speeches’ they left behind, ‘contrived on purpose to spread the poison wider, & foment fresh troubles' (17 July 1716, p. 109). He notes the Austro-Turkish war of 1716-1718; and the signing of the triple alliance between Britain, France and the Dutch republic.

Thomas’s letters to his friend and distant relative Sigismund Trafford contain society news and gossip. State lottery continues to feature prominently, and Thomas himself benefits from a modest windfall of £13. He discusses at length the first performance of Joseph Addison’s play Cato and reactions it has caused; and provides Trafford with a list of ‘New Books which are most read’, which include The Barrier-Treaty Vindicated [by Stephen Poyntz], Hiero; or, the Condition of a Tyrant [translated from Xenophon] and A Discourse of Free-thinking [by Anthony Collins] (30 December 1712, p. 14). In subsequent letters he describes the outrage the two last-mentioned books have caused among the clergy and the sermons from the pulpit they have occasioned. Thomas also describes the celebrations caused by the expiration of the three-year preaching ban imposed on the controversial high church clergyman Dr Henry Sacheverell (24 March 1712/3, pp. 23-24). In a later letter Thomas notes that ‘Dr Sacheverell is as great an Idol as ever, on the 31st of January there was such a Crowd to hear him, that they raised Ladders against the Church Windows’ (3 February 1714/5, p. 59). He describes the exceptionally wet summer of 1713 and its consequences, and follows with interest the progress of the general election in July and August 1713. There is a long gap in letters between Jan 1713/4 and September 1714 because Thomas is in France with [Benjamin] Lethieullier, youngest son of Sir Christopher and Lady Jeanne Lethieullier [née de Quesne].

Thomas’s personal life during the course of the letter book was wrought with sorrow. He records the death of his youngest niece [Mary Heigham?] on 13 April 1715 of ‘Rheumatism in her Stomack’ (19 April 1715, pp. 65-66); the death of his sister, Hester Heigham, which occurred on 24 October 1717 (2 November 1717, p. 127); and the death of his friend Lady Jane Lethieullier on 3 April 1718. Thomas’s aunt Margaret Crowther also died during the summer of 1718. Some of the letters deal with testamentary matters arising from her death, including the appointment of new trustees to the deed of settlement concerning the Free School of Weobley established by John Crowther in 1660 (23 January 1719/20, pp. 169-70; 18 February 1719/20, pp. 175-76) and 15 March 1719/20, p. 180).

Happier personal occasions include Thomas’s courtship of Olivia Western, to which he makes oblique references in 1717 and 1718 prior to the couple’s wedding in June 1718. He notes of his wife that ‘I have a great Prospect of being happy with her having chosen her more for the sake of her good qualities than any other Consideration whatsoever, & there are no Ladies in all this great Citty who have had a more serious education that those of that Family’ (3 June 1718, p. 141).

Following his marriage and the death of his aunt, Thomas’s letters are limited mainly to business matters, primarily the buying, letting and upkeep of property, ejectment of unwanted tenants, the collection of rents and tithes and the sale of trees. He also gives instructions for the building of a new farm house ‘of four Rooms on a Floor with Chambers above & Garrets over, & sellars [sic] underneath, & proper offices adjoining’ at Wormsley Grange, Herefordshire (27 February 1719/20, pp. 176-177), possibly the subsequent birth place of the classical scholar and theorist of the Picturesque, Richard Payne Knight.

Thomas White’s correspondents, in alphabetical order, are as follows:

Daniel Arthur

Paul Bertrand

James Brown

Mr — Browne ‘Attorney at Law at Bromyard in Herefordshire’

Mr — Carter ‘a Carpenter in Hereford’

Charles Childe ‘in Bath’

Samuel Collet ‘at the Postern in the Green Yard near Moregate’

Hannah Collins

John Copley

John Corder ‘at Stoke near Nayland in Suffolk’

Margaret Crowther

Benjamin Fallows ‘at Maldon in Essex’

John Fenwick ‘at Billingsgate’

John Floyd ‘at the Grainge at Wormsley near Weobly in Herefordshire by Weobly Bagg’

Thomas Franklin

Percyvall Hart ‘at Lollingstone in Kent by the Dartford Bagg’

David Jones

Rebecca Jones ‘at Dalstone’

John Littell

Williamson Lloyd ‘in Colchester’

Matthew Martin ‘at Wivenhoe in Essex’

Samuel Martin ‘at Whistaston to be let at Mr Carpenter’s a mercer in Weobly in Herefordshire’

Thomas Matthew ‘in Walbrooke’

Andrew Meade

Richard Morris ‘at Dalstone in Hackney’

Nicholas Morse ‘in Hoggesdon’

Richard Neave

John Newton

Nicholas North ‘in Mare Street in Hackney’

Francis Ram ‘at Stoke near Nayland in Suffolk’

Mary Ram

Mr — Robertson, ‘to be left at the post office in Lymrick’

Augustine Rock, merchant in Bristol

Richard Salwey ‘in Ludlow in Shropshire’

Joseph Sewell

Richard Skikelthorp

John Towns ‘at Stoke near Nayland in Suffolk’

Sigismund Trafford

Hannah Tuthill ‘at Kilmore near Lymrick’

John Tuthill ‘at Faha near Lymrick’

George Wade ‘at Christ College in Cambridge’ and ‘in Hartford’

John Walker ‘at Dalstone’

Abraham Ward ‘at Stoke near Nayland in Suffolk’

Edmond [Edmund?] Watts ‘in Watling Street’

Robert Weston ‘in Norfolk Street’

Mrs Wheake ‘at Marselles’

Jane Yates

The letter book contains White’s own pagination throughout, but there is an error in numbering, with p. 180 numbered as 110.

White, Thomas (1676-1742), English solicitor and landowner