Bound hardback letter book containing copies of some 1,200 letters sent by shipping merchant Samuel Monsell of Tervoe, county Limerick in the course of managing his extensive trading activities in Ireland, England, France, Holland and Spain. The letters deal in the main with the buying and shipping of goods, the insuring of cargoes and the complex financial transactions on which trading depended. The letters provide information on the names of ships and their captains going in and out of Limerick harbour, the cargo they contained and the fluctuating prices of goods over the years. The most common items in which Monsell traded included wheat, beans, hops, beef, pork, butter, tallow, hides, tanned leather, staves, coal, turf, salt, soap, candles, wine, vinegar and tobacco. The letters illustrate the difficulties of trading in perishable goods and the utter dependence of the business on good weather. In a letter to William Cleavland, written on 29 December 1723, Monsell notes that Captain Thomas Tarlton ‘was seen at the rivers mouth with 2 or 3 more sailes that has been outward bound and ready to saile these six weeks or 2 months past and the wind has Continued S. E. ever since till this morning.’ As a consequence of the vagaries of winds, trade fluctuated wildly between shortage and excess. Many of Monsell’s letters are written in response to queries from merchants seeking information on the current price of goods or attempting off-load goods that had flooded the market. On 8 September 1723, Monsell advised Robert Low of Liverpool that ‘this is no markett for leaf tobaco unless extraordinary good… sugars of noe kind will do here they are supplyed from Corke with refined sugars cheaper than you can afford…’

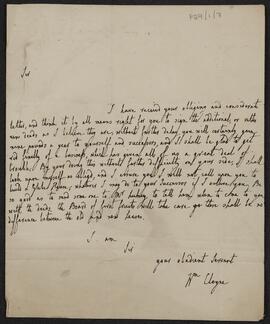

One way to protect goods was to ensure that the casks used for transportation were of the highest quality. To safeguard himself against potential loss, Monsell took extra measures as he explained in a letter to Arthur Hamilton of Liverpool, 24 September 1723: ‘I oblidge Every Cooper I deal with to burn their names att length on the Cask and any Cask that proves bad by leaking pickle they must pay for the barrell, att least itt will keep them in awe and make them take Care & Make their barrels good’. Insuring not only the cargo but also the vessel was paramount. Merchants often pooled together to hire a vessel, each insuring their own part of it. One insurer Monsell used was Joseph Percival of Bristol. On 26 May 1724, Monsell instructed him to ‘make the Insurance soe that in Case of Loss I should Recover soe much as I mentioned for the goods Cost me £815 Irish and the ⅛ of the Ship £64 English’.

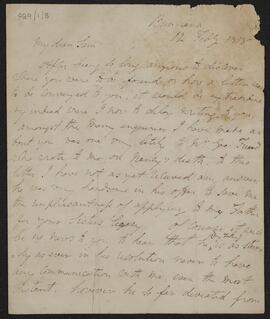

In 1724, Monsell had to deal with the failure of his Cadiz-based business, Monsell & Stacpole, and its near-catastrophic financial consequences. Tired of the high-risk nature of trading and constant delays in payments, he decided to retire ‘to my country house within 3 miles of the town’ and only ‘Export the produce of my owne grounds and resolve Intirely to Quit trading onely what I doe to Cadiz’ (Monsell o John Moniers, 9 April 1725). From this date onwards, Monsell’s letters deal mainly with land transactions as he set about increasing his estates in counties Limerick and Clare. In December 1723, he ‘purchased the Manor of Doonass which Cost me £3000 it is worth me about £400 per annum a Lease for 99 Years’ (Monsell to Messrs Monsell & Stacpole of Cadiz, 17 January 1724). Almost exactly two years later, he took ‘from our new Bishop my owne part and Twigs part of Mungrett as also I have purchased the fee of KilGobbin near Adare 262 acres of as Good Land as any I know… I have likewise Got Castle Ceale near Carrigoran for £1000… my Bargain In Castle Keale Is worth a Thousand pound more than It Cost me, with a little Improvement’ (Monsell to his son Samborn Monsell, 26 December 1725). In the end, he came to learn that land speculation was almost as wrought with complications as trading.

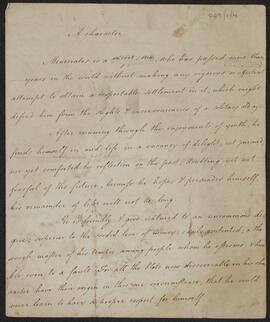

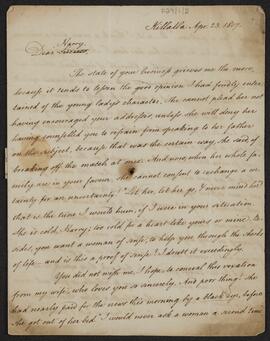

In addition to trading and land speculation, Monsell’s letters are rich in vignettes of other aspects of his life. He describes contentious council meetings, during one of which ‘Jack Roach began to use me with such freedom as I was nott able to beare… and was oblidged to make use of my Cane to Correct the old Raskell for his unmanerlyness…’ (Monsell to General Pierce in Dublin, 12 October 1725). In 1722, he purchased a wig but was obliged to return it to the manufacturer Francis Montgomery, it ‘not being fitt for my use tis neither full Enough of hair nor wide Enough on the head’ (18 October 1722). In November 1724, his life took a dramatic turn when he ‘had the Misfortune to have a dispute with a Gent in a narrow room & both our swords being drawn & my Servant man in & endeavouring to part us run himself in the Other Gents sword & recd it in his right breast of which he died Instantly[.] Thank God I have no hurt but one through my left hand which is in a fair way of doing well & the other Gent in his right breast which will likewise do well…’ (Monsell to Robert Adair, both 13 November 1724 ). The sword severed the tendons in Monsell’s hand and caused an injury from which he never fully recovered.

Monsell’s wife and children, particularly his three eldest sons, also feature prominently in his letters. He took care to provide his sons with a good education and find suitable positions for them. His eldest, William, who eventually succeeded to Tervoe, was sent to London to study law. The second son, Samborn, was set up in Dublin as a merchant, but proved a unreliable business partner to his father, repeatedly failing to deliver his messages or to act upon his instructions. Exasperated by his antics, Monsell warned him sternly to ‘for Godsake never omitt any business I give you on charge what you think may be no consequence may be of the most to me.’ (Samborn Monsell, 15 March 1727). When his third son, John, was about to set off on a voyage with shipment of beef, Monsell offered him this fatherly advice: ‘keep the men to their duty, pray take care how you behave yourself, for your life dont drink more than what you can well bear, nothing makes a man of business more ridiculous than being in drink & nothing recommends a man more than being a sober man…’ (24 December 1726).

The most frequent recipients of Monsell’s letters include his sons William and Samborn Monsell; the latter’s father-in-law Daniel Conyngham, merchant of Dublin; Monsell’s business partner Thomas Stacpole in Cadiz; merchants Arthur Hamilton of Liverpool, John Finlay of Dublin, John Monier of London, William Crosbie & Co. of Liverpool, Francis and William Lynch of Cork, Dublin, London and Nantes, Brian Blundell of Liverpool, Crisp Gascoyne of London, Edward Webber of Cork, James Browne of Dublin and William Cleveland of Liverpool; attorney Bryan McMahon; the private bank of Messrs Burton and Harrison of Dublin; Thomas Sinnott of Ratoath, Dublin; Messrs Harper & Morris of Cork; Sir Henry Hugh of Dublin; Messrs Webb and Addis of Limerick; Joseph Perceval of Bristol; and Lucy Southwell (née Bowen) of Dublin.